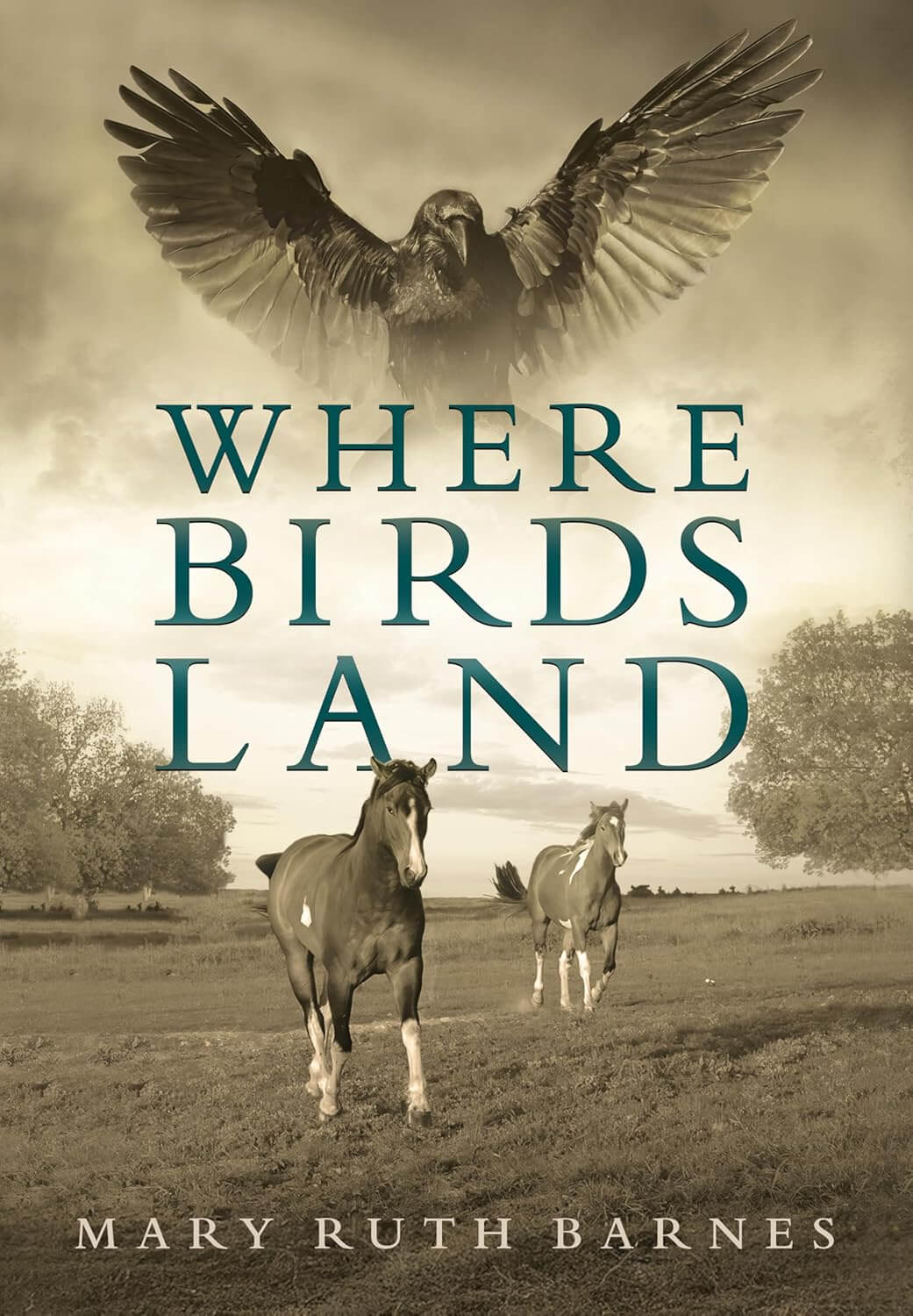

Mary Ruth Barnes is a Chickasaw artist, author, photographer, storyteller, philanthropist and historic preservationist. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English from North Carolina State University and received her master’s degree in education from Montana State University. After graduating college, Barnes taught high school and college English, art and computer science for 14 years. Barnes has won numerous awards for her art and short stories. She is known for her flowing, freestyle, vibrant depictions of outdoor scenes, First Americans and horses. Her specialties are watercolor and acrylic painting. Barnes’ love for nature is shown in her artwork, which is influenced by her Chickasaw family and experiences with storytelling. Her art reflects the colorful stories her Chickasaw grandfather shared. Barnes’ is also the author of Little Bird and the recently released novel Where Birds Land.

Where Birds Land is about my great grandmother, Ella Brown McSwain Adams, a Chickasaw woman who was forced to battle land grifters and a corrupt system during the onset of Oklahoma Statehood. It is a uniquely powerful story that history often overlooks. It was for her own survival that she decided to go up against the new laws of her new homeland. My grandfather Harry McSwain and his three sisters, my great aunts, shared numerous stories of their mother’s struggles with the Dawes Commissioners. The Dawes Commissioners were a group of five functionaries hired by the government during the time frame of 1887 to 1906 in Indian Territory, to determine who was Indian and who was not.

Ella was desirous of land, a rightful allotment, but that land was usable for raising cattle and horses, and growing crops, all essential to her survival and her family’s survival. I found over 75 pages of Ella’s battle with the Dawes Commission on Ancestry. It was documented that she was refusing the acceptance of the land that was offered her, because if she accepted it, the land would be placed in a trust, and she could not sell or lease it for twenty-five years. This was created under the umbrella of the Dawes Act of 1887. She knew if she accepted it, she would be stuck with a useless piece of rocks.

Ella’s husband John Adams, wrote to the Commissions stating this: “I went over the land, almost every acre and found that it was unfit to cultivate, it could not grow grass, had nothing on it, but weeds. I found that I could neither lease it nor rent it.” Later, John Adams wrote again to the Secretary of Interior and said, “ My wife who has directed me every step of the way during the writing of this letter, is sitting while I write this letter. I have no interest in this matter other than the grounds of principle. Any white man who would take an Indian woman and mislead her as they have done, is too infamous to run at large and should be prosecuted according to the law for false swearing and perjury.”

As I further dissected the transcripts of her interviews with the Dawes Commission, I found that some land grifters were trying to challenge her that they had already been gifted the land on the side of this property could be cultivated. She was determined that this man, who had confronted her and children when they tried to survey the property, would never get this property from her if she were ever allowed to sell it. My research then directed me to the county clerks’ office in Ardmore, Oklahoma, to see when and to whom she eventually sold her property. I discovered that each time Ella and children sold their allotments in this area it was to the same individual, only to discover that a few weeks later that person resold the land to the landgrifter who wanted the property from her originally. That land then went for the sum of $1. It became apparent that this man, who purchased the property, was just the middleman, working for that land grifter. Not only were relatives swindled once, but twice! This inspired me to continue writing of my families’ saga of indigenous dispossession and to make a voice for Ella’s fight to hold on to what was rightfully hers. Ella’s defiance created a drive in me to even dig deeper into the Dawes documents and interviews. In that research, I found an 80-page document of Ella and four minor children vs. the United States Supreme Court. It was this court document that compelled me to spotlight the strength of Ella’s defiance.

After I felt I had exhausted all of the Ancestry files available to me about her, I decided to see what I could find in actual newspapers during that time frame. Newspapers is not an easy search. I looked for just her name in any articles I could find. I found more land on the Blue River that she owned, and in that article, it stated that other land grifters were trying to steal that land as well. It was the land her grandfather grew up on and now she was also fighting for some inherited land that was being distributed to others during the land rush of 1889. It was once again, a “stolen legacy” that many indigenous people went through during that time.

Further developments followed, as I pursued articles about Bloomfield school where her daughters, Minnie, Bessie and Romey attended. I knew that the Superintendent of Bloomfield was fired when they attended there, but I never found out from them why. They obviously did not want to share that story with me. I read numerous books on Bloomfield school without finding any reason for the Superintendents’ dismissal. And then, an article appeared, headlining his firing and within that article were the names of my great aunts, Minnie, Bessie and Romey. I cried at what happened to them and from that one article I was able to recreate an emotional event that probably ripped my ancestors apart when it happened. You have to read my book to get the full details of what happened.

These events and stories are not just my family story, but the story of many families in Indian Territory. They removed from their original homeland to Indian Territory, and then again from this new homeland. These indigenous people were resilient and courageous, and I hope my story will capture these historical times, appealing not only to our Native American audiences but creating a visual story for all who appreciate the weight of the past and what it means to all Americans, as we look to the future.

Where Birds Land by Mary Ruth Barnes

Ella McSwain faces the perilous task of raising her family whilst protecting them against the growing threat that is the new state of Oklahoma as a Chickasaw woman. All she is left with to her name is a destitute plot of land, but she plans to fight for her proper share. Can she win her fight when the whole deck is stacked against her?

Buy the book now: Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble

Leave A Comment