Shelley Noble is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of Whisper Beach, Beach Colors, and The Tiffany Girls, the story of the largely unknown women artists responsible for much of Tiffany’s legendary glasswork, as well as several historical mysteries. A former professor, professional dancer and choreographer, she now lives in New Jersey halfway between the shore, where she loves visiting lighthouses and vintage carousels, and New York City, where she delights in the architecture, the theatre, and ferreting out the old stories behind the new. Shelley is a member of Sisters in Crime, Mystery Writers of America, Women’s Fiction Writers Association, and Historical Novel Society.

With contemporary fiction we can depend on the reader to fill out much of the detail. If John reaches for a Kleenex, the reader can imagine the rest, but if in 1870, Molly picks up her box of Dr. Hopper’s Female Pills, we have some explaining to do. And do it while advancing the story and emotional arc of our characters.

Historical fiction is more detail reliant. In historical fiction, there is much that is unfamiliar that is important to the story and that we want our readers to understand. We fall in love with our subject and want them to love it as much as we do. Fearing that it won’t be clear, we overload the page with, to us, the wonderful details, and what editors might call the dreaded “info dump.”

Details are more than descriptive adjectives and adverbs. There are places for a paragraph of description, a brief telling and showing. But such versatile tools can quickly become the weeds of fiction. There’s a fine line between giving the reader enough, so they don’t feel in the dark and have to stop reading to look things up, or explaining so much that they forget why they cared about the story.

One of their most important duties of description in historical fiction is to explain things that are unfamiliar and without having to stop the narrative to do so. How details are used are key elements to the success of a historical story.

Details gain strength and immediacy by weaving them into each scene, making the scene richer, stronger, more developed, while propelling the story forward. They do this by becoming integral with the other elements of fiction.

Characters

Characters are our invitation and subsequent understanding and investment in their world. The more a reader identifies with the characters, the more seamless their experience of the uniqueness of their world will be.

Period

The clothes are different, the manners are different, the mores are different. Sure, we can do an introductory sentence or two, but the POV character interacting in her world sets the stage more immediately. It just takes a little attention to present descriptions as seen through the sensibilities of the characters, while still sounding modern enough not to be off-putting.

Setting

Town? Country? Secluded island? Seeing detail through the eyes of the POV character makes the scene more vivid than a bird’s eye view by an unseen narrator. (Though those sometimes have their uses.) Details easily become a jumble if they’re all presented at once. The character doesn’t see everything at once and the reader shouldn’t have to.

Plot

It’s all in the detail. As the story progresses, it is important not to let it get hijacked by suddenly or belatedly introducing an object, a person, an event that needs to be explained. A real momentum killer. There may be other earlier places that can be set up for when we reach that part of the story, so that a shorthand description suffices. The reader doesn’t need to know everything. They can research it later, don’t make them stop reading to look it up.

Emotion

This is one of the best two-way streets between character and detail. Whether the character’s emotion pinpoints the important detail, or a detail sets off the emotion, that’s an active moment, and consequently more memorable.

None of these elements exist exclusively in their own lanes. They all interact, incorporating details to make the story make sense.

Let’s pop back in on John and Molly.

“Kleenex” lays out a lot of information and needs little description, it offers us a short cut. What detail you decide to use depends on the need of the scene. If John takes a tissue, blows his nose and drops the used tissue in the trash, it’s probably not important whether the box is square or rectangular or what color the tissue is. But if he snatches it up in a panic, sending the rectangular box flying across the floor, scaring the cat, and shoves the tissue toward an inconsolable Sue… we still don’t need to know more about the tissue.

Historical fiction is more detail reliant. In Molly’s story, the introduction of Dr. Hopper’s “Female Pills” signals that the story is in the past. How much does the reader need to know about them?

The pills come in a little rectangular box, with a slide tray, a little larger than a match box, with red and black lettering across the top. Learning this does nothing to advance the story. How much the box figures in the scene will determine how much detail is needed. By introducing the box via the five story essentials above, we can control how and when they become part of the story. If they’re just Molly’s vitamins, maybe we don’t need to know the full description of the box. But if later, we find Molly dead with the pill box in her hand…or the pills that killed the Major came from a box that looked exactly like Molly’s vitamins…

Molly is in her bedroom, alone, and she slips the little rectangular box from her skirt pocket with trembling fingers…already we probably want to know more. We’re pulled into the narrative; this isn’t the time for a history, medical, or manufacturing lesson. We suddenly have a story question. What’s wrong with Molly that she needs pills? Why is she frightened?

All just in one sentence. Molly slowly pushes the little cardboard tray open, the red and black outline “Female Pills” blurring before her eyes, but she can’t look away. Somewhere in the house a door slams. She startles, upsetting the boxand casting a sea of little blue pills across the pink sateen bedspread. She frantically tries to return them to the box. Three box details are presented in two actions. An emotional reaction about the pills and three physical reactions accomplish what the list did, only more. Meshed with Molly’s feelings and her setting, the “list” of details becomes a dynamic presentation.

By incorporating the details into the action, setting and emotions of the character the author brings the reader into the story, tightens the interest, as well as describing specifics that might be unfamiliar and will possibly be important later in the story. We haven’t told the reader exactly what the pills are for or why Molly is so upset and is desperate to hide them, but an idea has been planted. And hopefully they’ll keep reading to see what happens next.

One little caveat. Research is so important. Be precise, fudge only when you must and don’t take common knowledge for granted. For example, don’t assume because blue and pink (Molly’s pills and bed spread) are boy’s and girl’s colors. They weren’t in 1870. Know more than your reader.

A balanced and integrated use of detail can propel the reader into a different time and place among unfamiliar people while delivering a full-blown experience as vivid and amazing as the frames of an HBO or Netflix saga. It just takes a few well-chosen words.

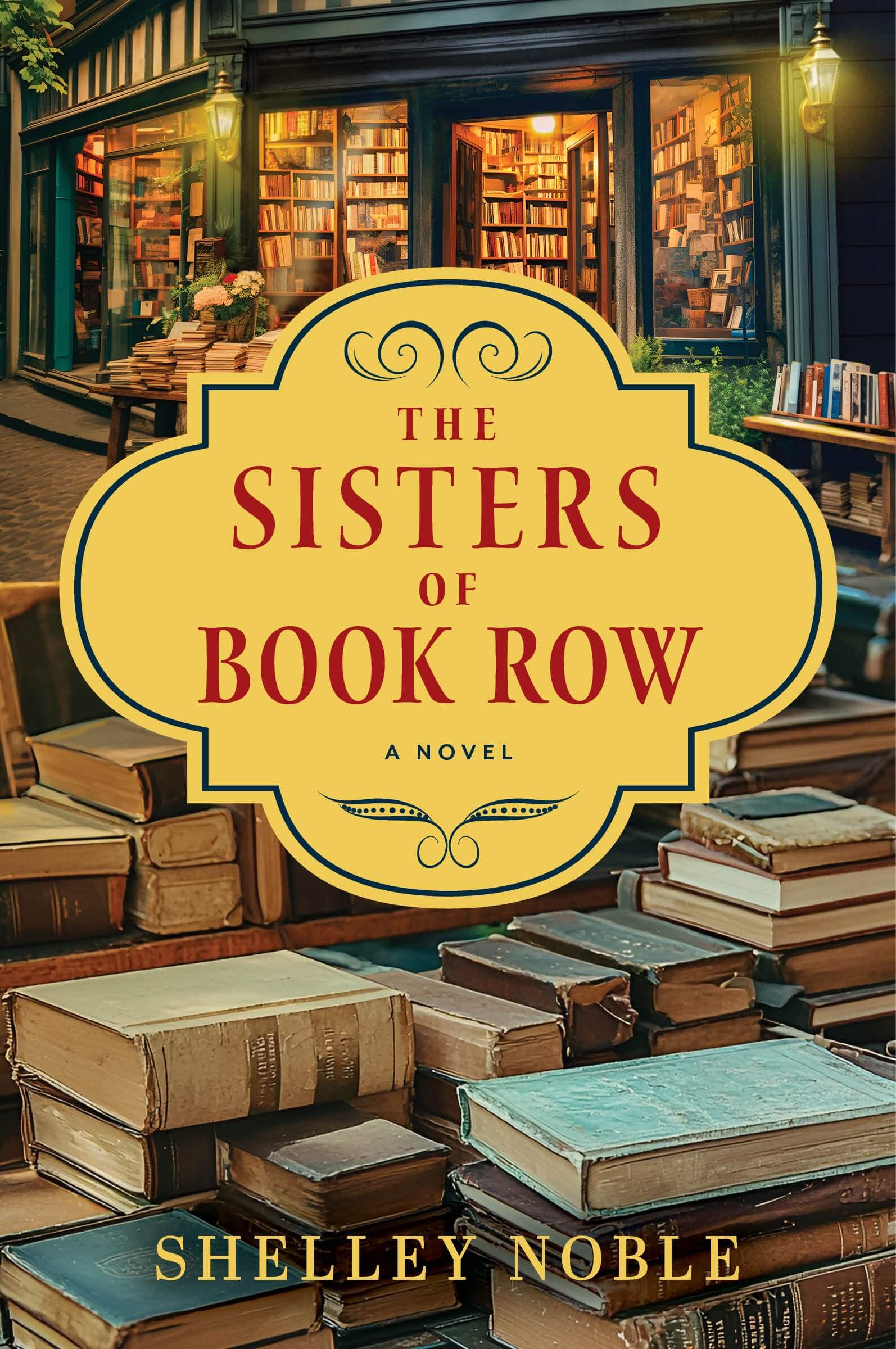

The Sisters of Book Row by Shelley Noble

In 1915 Manhattan, the Applebaum sisters run the Arcadia Rare Bookshop amid the bustling Book Row—until the notorious moral crusader Anthony Comstock sets his sights on their world. As the Comstock Laws threaten to criminalize even classic literature, youngest sister Celia secretly joins an underground movement printing women’s health information hidden inside books. When secrets, danger, and a mysterious stranger converge, the sisters must fight to protect both their family and the freedom of the written word.

Leave A Comment