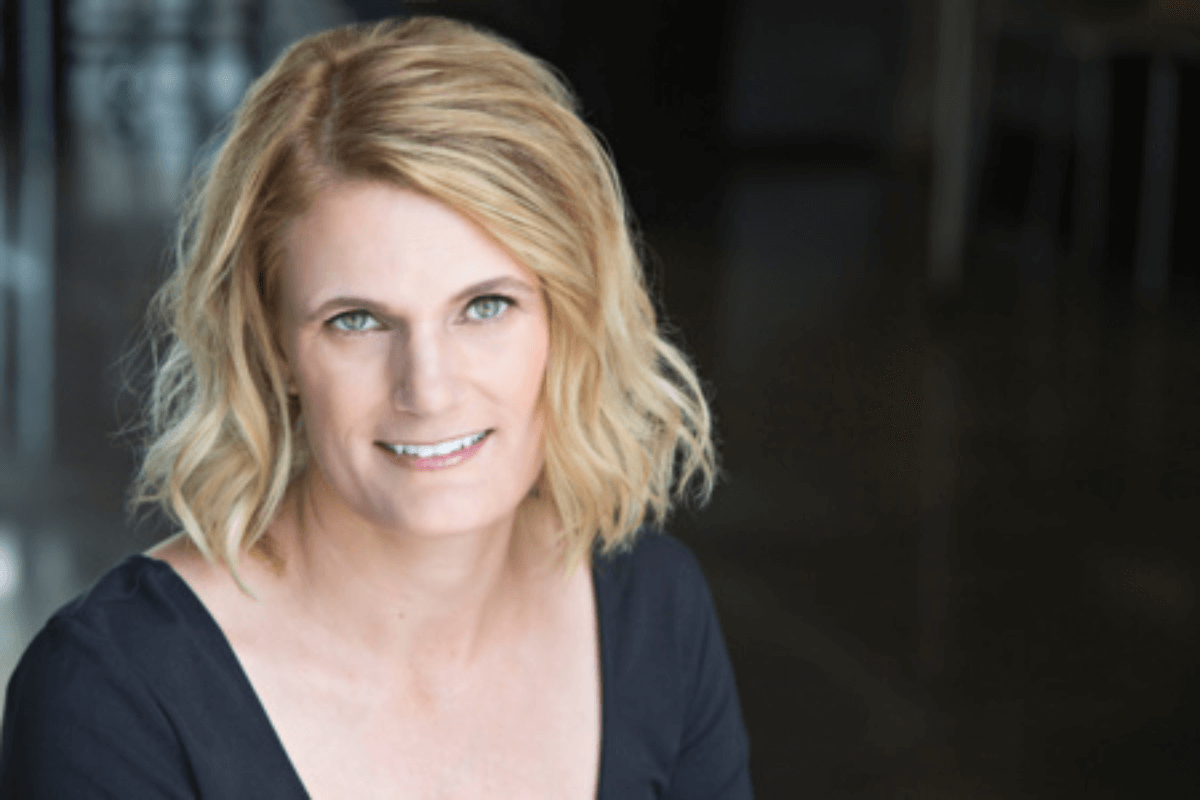

She Writes had the opportunity to sit down with the inescapably brilliant author Maggie O’Farrell following the adaptation release of Hamnet. We got the chance to talk about what it was like collaborating with Chloe Zhao on the film, what she most loved about the adaptation, her best writing advice, how the publishing industry has changed for women in her 25-year career and more.

On Seeing Hamnet on Screen

She Writes: As you watched the adaptation of Hamnet, what were you most looking forward to seeing played out on screen?

Maggie O’Farrell: I think my favorite part of the film, particularly compared to the novel, is the final sequence—the last ten minutes in the Globe Theatre. In the novel, that section is quite compressed. You can’t really include long, undigested chunks of Shakespeare on the page; it just doesn’t work structurally. Readers can’t be expected to read through an entire speech and then return to the action.

But on screen, you can do that. You can hear large portions of the play, see the actors performing it, witness the sword fighting, hear the clash of steel… it’s thrilling. It becomes a fully cinematic experience, and that was incredibly moving for me.

Writing for the Page vs. Screen

SW: Do you feel like seeing one of your stories told on screen will change how you write or approach your novels?

MO: I don’t know. It’s interesting. I do think that writing fiction and writing screenplays use very different muscles, different parts of your brain, in a sense. Obviously there’s overlap: a sentence is still a sentence, dialogue is still dialogue. But they ask very different things of you.

A reader interacts with a book in a very solitary, interior way, which is very different from an audience watching a screen, especially in a cinema, where it’s a collective experience. I love the idea that a cinema audience is replicating the experience of a Globe audience on screen. I love the mirrored effect of that.

Collaboration and Adaptation

SW: What was your collaboration experience like on the film?

MO: It was fascinating. As a novelist, you’re used to working alone, just you and the page. But with a screenplay, especially because Chloe Zhao and I co-wrote it, the process is very different.

Chloe and I come from different backgrounds, different cultures, and different generations, but we share a deep love of storytelling. One of the first things we discovered was that we had the same favorite filmmaker, Wong Kar-wai, which surprised us both.

Chloe brought a very clear vision to the adaptation. Hamnet is a fairly long novel, and the first job was to strip it back because a screenplay is only about ninety pages. A great deal has to be let go. We also had to unravel the chronology. The novel moves back and forth in time, which works on the page but can feel disorienting on screen.

Another challenge was externalizing what is a very interior novel. Much of the book takes place inside people’s minds and hearts, and film requires those emotions to be made visible. The whole process reminded me of an hourglass: you begin with a wide, expansive novel, narrow it down to its bare bones for the screenplay, and then watch it widen again into something entirely new through performance, visuals, and sound.

SW: The acting was phenomenal.

MO: Truly. Jessie Buckley, Paul Mescal, Emily Watson, and the children. Every one of them brought such dedication and depth. You could feel it in the theater.

Writing Shakespeare Without Writing Shakespeare

SW: Writing about Shakespeare must have been daunting. How did the idea first come to you?

MO: It came gradually and with a lot of vertigo. I’d loved Hamlet since I first read it at sixteen. My English teacher mentioned, almost in passing, that Shakespeare had a son named Hamnet who died at eleven, and four years later Shakespeare wrote Hamlet.

That connection—the names, the play, the ghost—always felt hugely significant to me. Yet Hamnet was reduced to a footnote in his father’s story. That didn’t sit right with me.

I was very nervous about writing a novel connected to Shakespeare. At times I thought it was a wonderful idea; at other times, a terrible one. What helped was removing his name entirely. His name never appears in the book. Writing sentences like “William Shakespeare came downstairs and had breakfast” felt impossible. Once I removed the name, the story could breathe.

SW: It really reorients the story around the family.

MO: Exactly. Biographers focus on his life in London, where his career happened, but it never made sense to me that his family would be absent from his inner life. I wanted to shift the focus to them.

Grief, Art, and Aftermath

SW: The novel focuses heavily on grief. What advice would you give writers trying to capture such a raw emotion?

MO: It was important to me that the story didn’t end with Hamnet’s death. What happens afterward—the next four years—is just as important. That part of the story is about where art comes from and why we need it. We need stories to explain ourselves to ourselves.

When you read Hamlet through the lens of the loss of a son, the play feels like a message from a father in one realm to an unreachable child in another.

On History, Silence, and Women’s Stories

SW: Shakespeare’s early life is sparsely documented. How did that affect your approach?

MO: I would bow down in awe of any biographer. I think it’s an incredible job. You have to have the mind of a detective, a writer, and a scholar, it’s astonishing. And yet, despite all their best efforts with Shakespeare, there is still so much we don’t know about him.

In contrast to his enormous body of work, which we only have because his friends published it after he died, he left a very light paper trail. By comparison, Marlowe and Jonson published their plays during their lifetimes because they wanted them preserved. Shakespeare didn’t do that, which I find fascinating. He retired, he had several years in Stratford, so he could have done it if he’d wanted to. Obviously, he didn’t. And I find that really intriguing. Did he not realise what he had? Did he not realise what he’d done, that it should be preserved?

So we have this extraordinary body of work, but on the other hand, we have remarkably little documentation about the man himself. There are, I think, ten times more documents about his father, John, than there are about William. Partly that’s because John kept getting into trouble with the law—which is another story entirely. But that was how records were kept in those days: if you were naughty, you left a paper trail.

There has been so much incredible scholarship and detective work done, but there are still things we simply don’t know. Shakespeare remains quite an elusive figure. And when it comes to his family—his wife, his daughters, his son—we know even less. They’re very shadowy figures.

One thing about the entire Shakespeare biography industry that always breaks my heart is this: his daughters, Susanna and Judith, both lived into their seventies, which was astonishing for that time, when the life expectancy was around forty-eight. They lived almost twice as long as expected. And around the time they were elderly women, the first Shakespeare biographies were being written. Yet not one of those biographers thought to go to Stratford-upon-Avon and ask them, “What was he like? Tell us about him.”

That breaks my heart, because of what we might have had if just one person had bothered to ask that question and gather their impressions. But nobody did. And that loss is forever.

SW: You’ve spoken before about women’s stories being sidelined. Do you feel the landscape is changing?

MO: I hope so. I mean, certainly when I started out twenty-five years ago there was a very definite idea that there was fiction, and then there was women’s fiction, which was treated as a completely separate category. That’s very strange when you think about it, given that women make up roughly fifty percent of the population.

I remember journalists asking me, “Why is it that you write women’s stories?” And I would say, “Well, I am a woman.” Why wouldn’t I? And I’d often follow that by asking, not in a rude way, “Do you ask men the same question?” Do you ask Ian McEwan why he writes men’s stories, or Jonathan Franzen? Of course not. It’s such a strange question.

But I do think things have improved. When I was a journalist in the late nineties, working on books pages, women simply didn’t get the same reviewing space that men did. That imbalance was very clear.

I think there’s been a significant shift since then. Writers like Hilary Mantel, Anne Patchett, Bernardine Evaristo—these huge literary behemoths—have really changed the landscape for women. And I hope that now we’re no longer seen as a subgenre, but simply as fiction writers, because that’s what it is.

Writing Without Fear

SW: You’ve spoken about taking a more relaxed approach to writing. In an industry that can be rather anxious, how did you arrive there? And what advice do you have for other writers?

MO: Well, on the door of the room where I work, I have a postcard of Tove Jansson, the Finnish writer who wrote The Moomins. It’s a photograph of her—possibly taken by her partner—swimming in the Finnish archipelago. I think she’s probably naked; you can’t really see, but I suspect she is. She’s wearing this enormous flower crown on her head and has the most blissful smile on her face. It’s just a glorious photograph.

So I keep that postcard on my door, and whenever I’m feeling that kind of “Oh God, this is so difficult, I hate my work” feeling, I look at it and think, actually, Tove Jansson has a point. You have to remember that it’s an enormous privilege to live the life of an artist, and of a writer.

Obviously, there are economic considerations, and it isn’t easy. I’m very lucky now that I don’t have to worry too much about paying the mortgage, and I do realise that. But I also think you have to hang on to the idea that you’re doing what you love. And you are.

I know that often you have to have other jobs—I’ve been through a lot of that myself. You need something to support yourself. But even so, you’re carving out time to do what you really want to do. And I think that’s something you have to remember. That’s why I keep that postcard there: to remind myself of the upside of being an artist. Because if you’re an artist and you’re getting to create your work, whatever it is, you’re really lucky.

Quickfire Questions

SW: What’s a great book you’ve read recently?

MO: I read something quite recently, it’s a slim volume called Clear by Carys Davies. It’s a really wonderful story set during the time of the Highland Clearances in Scotland. A reverend, has to go to a very remote island to tell the final inhabitant that he has to leave.

It’s really surprising. It’s a beautiful novel. Very much like its title, the prose is very clear, very spare, but it completely pulls the rug out from under the reader. I was genuinely surprised by it twice, which I absolutely love. I love it when a book’s plot really, truly surprises me.

SW: What’s one book you always recommend to people?

MO: Oh, so many. I always say to people—especially if they want to be writers—you have to read The Color Purple.

I think it’s an absolutely perfect, brilliant, challenging, confronting novel. Celie’s voice is so immediate right from the first page, you know exactly who she is. I always tell people to read that.

I also love something really experimental and wild. I love Annie Proulx, I think she’s fantastic. Barkskins is a book I give to people over and over again. And something really out there, like A Visit from the Goon Squad. I love that book. I often give it to people when they say, “I don’t know what to read at the moment.” I always say, try this, it’ll hit like a cold wave.

SW: What’s your best piece of writing advice?

MO: What I wish someone had told me when I was starting out is that you don’t have to begin at the beginning. I find beginnings really hard. They’re hard because you have to establish the story, find exactly where you want to start, set everything up, there’s so much to do that it gives you terrible vertigo, and often you never start at all.

Then I realized, actually, you don’t have to. You can just dive in. It doesn’t matter. You just have to get writing. You can make bad writing good, but a blank page is always just going to be a blank page.

SW: There’s so much pressure around page one, line one, chapter one.

MO: It’s hideous. I never do it either. I always go back halfway through and then write the beginning to match the end. I find it really liberating.

SW: What’s one of the best moments of your career so far?

MO: Oh, goodness. Probably two things. Winning the Women’s Prize—that was pretty exciting. And standing in the middle of the reconstructed Globe for the film. That was also pretty extraordinary.

SW: What are you working on next?

MO: I’ve just finished a new book. It’s coming out in June, and it’s called Land. It’s set in Ireland in the second half of the nineteenth century, just after the famine.

Preorder the book now: Bookshop.org | Amazon

Leave A Comment